|

COURSE OUTLINE

Introduction and Course Overview

Learning Objectives

Pain as Disease

Chronic Pain as Disease: Why Does it Still Hurt?

The Experience of Pain

A Definition of Pain

Categorizing Pain: Acute, Recurrent Acute, Chronic

Acute Pain

Recurrent Acute Pain

Chronic Pain

Chronic Pain Associated with a Progressive Disease

Chronic Non-cancer Pain

Chronic Neuropathic Pain

Chronic Pain versus Acute Pain

Theories of Pain

Old Ideas: The Specificity Theory of Pain

Problems with the Specificity Theory

New Ideas: The Gate Control Theory of Pain

Down the Pain Pathways

Opening and Closing the Gates

Patient Examples: The Gate Control Theory in Action

When Acute Pain Becomes Chronic

Chronic Pain and Suffering

The Pain System

The Multi-factorial Nature of Pain and Suffering

Tissue Damage or Nociception

Pain Sensation

Thoughts

Emotions

Suffering

Pain Behaviors

Psychosocial Environment

Factors Influencing Acute and Chronic Pain

Chronic Pain and Depression

Depression and Chronic Pain

Depression and Spine Surgery

Treating Depression the Chronic Pain Patient

Chronic Pain and Anxiety

Chronic Pain, Fear and Phobia

Chronic Pain and Anger

Chronic Pain and Entitlement

Other Factors Influencing Pain and Suffering

Positive Reinforcement of Pain Behavior

Avoidance Learning

Reinforcement by the Medical Community

Difficulty Coping with Being Well

Conclusions

Resources

References

INTRODUCTION AND COURSE OVERVIEW

Many disciplines provide psychological treatment of chronic pain patients. Some examples include psychologists, psychiatrists, clinical social workers, nurses, physicians’ assistants, marriage and family counselors, psychotherapists, counselors, among others. In this series of online courses (Chronic Pain Management I, II, III), the term “pain management clinician” will be used to encompass all of these practitioners.

Working with chronic pain patients requires a special skill set for the pain management clinician. One of the most important issues is to have a good understanding of current pain theories and the nature of the chronic pain syndrome since this forms the rationale upon which psychological interventions are justified to the patient. The first course in the series will provide an overview of a definition of pain, different classification systems for pain, as well as outdated and current theories of pain.

This course will also discuss various factors that can influence a patient’s perception of pain and overall level of suffering. The multi-factorial influences on pain will be reviewed including tissue input (nociception), pain sensation, thoughts, emotions, pain behaviors and the psychosocial environment. Factors impacting the transition from acute to chronic pain will be discussed.

Chronic Pain Management II – Psychological Evaluation and Treatment, the second course in the series, will review a model for the biopsychosocial assessment of the chronic pain patient. This model is based upon a “targets” of assessment approach developed by Belar and Deardorff (1995, 2008). Methods of assessment for use with the chronic pain patient will also be presented including the clinical interview, questionnaires, patient diaries, psychometric testing, behavioral observation, and reviewing archival data. A template for the chronic pain evaluation report will also be discussed. This second course in the series will also present the most commonly used “direct” psychological treatments for chronic pain including cognitive-behavioral interventions and deep relaxation training.

Chronic Pain Management III – Special Issues will review common medical areas of treatment in which the pain management clinician acts in collaboration with other healthcare professionals. In working with medical disorders, the pain management clinician must be comfortable interacting with the patient’s other providers (e.g., physician, physical therapist, etc). This course will discuss the pain management clinician’s role in medication management, long term opioid treatment, helping to design a physical rehabilitation program based upon behavioral principles, and spinal cord stimulation.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

This is a beginning to intermediate level course. It is the first in a three part series on chronic pain management. After taking this course, the health care professional will be able to:

· Discuss current theories of pain including the gate control theory

· Explain a model for understanding and treating chronic pain

· Explain the difference between acute, recurrent acute, and chronic pain

· Discuss psychological factors that affect acute and chronic pain

· Explain the difference between pain and suffering

PAIN AS DISEASE

This section will provide an overview of current theories of pain. The material will be presented in a straightforward and concise manner. The goal of this section is to provide the practitioner with an overview of the important concepts while also presenting the information in a manner that can be used when working with chronic pain patients. Giving the patient an understanding of the multi-factorial nature of chronic pain is essential to the success of any psychological intervention.

Chronic Pain as Disease: Why Does It Still Hurt?

People who suffer from severe, chronic pain know how it can utterly disrupt and damage one’s life. Pain can be cruel making it hard to enjoy even the simplest daily activities, and certainly making it a challenge to carry out an exercise routine and other healthy activities. Moreover, chronic pain was not previously that well understood. The medical profession used to believe that pain is always a manifestation of an underlying injury or disease. As will be discussed subsequently, it was also believed that the amount of pain correlated highly (almost one-to-one) with the amount of tissue damage or injury. As such, doctors focused on treating the underlying cause with the belief that once the injury or disease was cured the pain would then disappear. If no underlying cause could be found, then the patient was told that very few treatments are available or worse, “the pain must be in your head”. Unfortunately, some physicians still practice in this manner, having no appreciation for the unique problem of chronic pain, newer theories about pain, and the many factors that influence a chronic pain problem.

The medical community is starting to understand that if pain is no longer a function of a healthy nervous system (signaling that there is a disease or underlying injury), then the pain itself becomes the problem and needs to be treated as the primary pathology.

The Experience of Pain

To successfully treat a chronic pain patient one must accept that all pain is real. This may seem like an obvious statement, but people with chronic pain are often treated as if their pain is either imaginary or exaggerated. Some of this is perpetuated by the mind-body dualism inherent in the medical model. Unfortunately, this model continues to be alive and well in the medical community. Mind-body dualism espouses the old dichotomy of “functional vs. organic” when evaluating and diagnosing chronic pain. In the model, functional pain is conceptualized to be of purely psychological etiology. A patient is often given this label by his or her physician if a precise reason for the pain cannot be found (identification of a pain generator). In this scenario, the psychological etiology is a diagnosis by exclusion. Given this situation, it is not surprising that many chronic pain patients feel like they have to prove their pain to their friends, family and doctors. There are countless patients with stories of being told by doctors that there is no “medical” reason for the pain and therefore “it cannot be that bad”. One of the first tasks of the pain management clinician is to establish with the patient that his or her reports of pain will be believed. This is especially important since the patient may be hesitant about seeing a “shrink” in the first place. We will discuss this issue further under the initial interview section.

Working in this field is challenging since chronic pain is somewhat of a unique medical problem. Pain is a personal experience and cannot be measured like other problems in medicine such as a broken leg or an infection. This causes a frustrating experience for the chronic pain patient in interacting with the healthcare system, family and friends. Everyone knows that a broken leg can be confirmed by an X-ray and an infection by a blood test measuring white blood cell count. Unfortunately, there is no medical test to measure pain levels. To make matters more challenging for the chronic pain patient, there may be no solid objective evidence or physical findings to explain the pain. Thus, chronic pain sufferers will go from one doctor to the next searching for medical explanations for their pain (and a cure). This can lead to unnecessary evaluations and treatments, in addition to putting the patient at risk for actually being harmed or made worse by the interventions.

A DEFINITION OF PAIN

Pain is not easy to define. In 1979, the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) published its first working definition of pain:

“An unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage”

This definition was reaffirmed in 1994 along with an extensive footnote discussion regarding its implications. The IASP definition acknowledges that, for most people, tissue damage is the “gold standard” by which pain is understood. However, the definition also recognizes that pain may occur in the absence of tissue damage and is impacted by emotional (psychological) factors. In the footnote explaining the definition, the authors point out that pain is not equivalent to the process by which the signal of tissue damage is passed through the nervous system to the brain (this is called “nociception” and will be discussed in detail later); rather, pain is always a psychological state that cannot be reduced to objective signs. In other words, pain is always subjective.

As shall be discussed later, the pain definition takes into account the following research findings:

· Extensive tissue damage may occur without pain

· Pain may occur in the total absence of tissue damage

Since pain is subjective, everyone experiences and expresses it differently. The IASP definition takes into account research which has demonstrated that individuals with the exact same injury will feel and show their pain in unique ways depending on a number of things such as:

· The situation in which the pain occurs.

· Thoughts about the pain such as “this is nothing serious” versus “this pain could kill me”.

· Emotions associated with the pain such as depression and anxiety versus hopefulness and optimism.

· Cultural influences determining whether a person is to be more stoic or more dramatic in showing pain to others.

The newest theories of pain can now explain, on a physiological level, how and why people experience pain differently. The newer pain theories will be discussed in detail later along with clinical and research findings about situational, cognitive, affective and cultural influences on pain.

CATEGORIZATING PAIN: ACUTE, RECURRENT ACUTE, CHRONIC

Understanding how pain is categorized is critical to providing proper evaluation and treatment. The classification of pain is not a straightforward task and there is no one system that has been universally accepted by clinicians or researchers. As discussed by Gatchel (2004) and others (Turk and Melzack, 1992), there are many ways that pain can be classified including:

· by the disease state causing the pain or “diagnosis” (e.g., arthritis, cancer, diabetic neuropathy)

· by the mechanism of the pain itself (e.g., neuropathic, musculoskeletal)

· by the age of the sufferer (pediatric, pain in the elderly)

· by temporal profile or duration (e.g., acute, chronic, recurrent)

Probably, the most common classification that is used is temporal. As Gatchel (2004) points out, this is likely due to the fact that the temporal classification best helps to understand the biopsychosocial contributors to the pain problem as well as guiding evaluation and treatment. However, it should be kept in mind that a simple temporal classification also has problems since it does not take into account acute recurrent pain (periodic acute pain episodes with pain-free periods in between) and tends to ignore pain conditions associated with a progressive disease process (cancer, COPD). For the purposes of this discussion we will review the common temporal categories of pain along with modifications to take into account acute recurrent pain and pain associated with a disease process. In this schema, pain can be separated into acute, recurrent acute and chronic. In addition, there will be sub-categories of chronic pain.

Acute Pain

Acute pain is usually indicative of tissue damage and most often serves a protective function for the body signaling potential physical harm. Acute pain can be defined as follows:

· pain that is associated with tissue damage, inflammation, or a disease process.

· pain that is of relatively brief duration (e.g., lasting less than 3 to 6 months)

This is the kind of pain that you experience when you cut your finger or stick yourself with a needle. Other examples of acute pain:

· Touching a hot stove or iron: This pain will cause a fast, immediate, intense pain with an almost simultaneous withdrawal of the body part that is being burned. You might then experience more of an aching pain that occurs a few seconds after the initial pain and withdrawal.

· Labor pains: The pain during childbirth is acute and the cause is certainly identifiable

· Smashing your finger with a hammer: This pain is similar to that of touching a hot stove in that there is immediate pain, withdrawal and then “slower” aching pain.

In acute pain there is likely to be a one-to-one relationship between the amount of tissue damage and the pain experience. In addition, the pain will tend to subside in correlation with tissue healing. Acute pain is often associated with some anxiety that will motivate the individual towards adaptive and self-protective behavior (e.g., resting the injured body part during tissue healing, seeking medical attention, etc).

Acute Recurrent Pain

In acute recurrent pain the individual suffers from pain episodes with pain-free periods in between. The pain episodes are usually brief (e.g., less that 3 months) and associated with an identifiable physical process (such as migraine headaches, sickle cell anemia, back sprain, etc).

Chronic Pain

In contrast to acute pain, chronic pain is usually less indicative of tissue damage and generally does not serve a protective function for the body. A temporal definition of chronic pain is as follows:

· pain that occurs past the point of tissue healing or,

· pain that lasts more than 3 to 6 months

As discussed previously, this definition emphasizing the temporal component is not completely adequate for all types of chronic pain problems. Even so, the psychological principles of chronic pain assessment and treatment remain the same. There are at least three types of chronic pain problems: (1) chronic pain that is due to a clearly identifiable cause or process, (2) chronic pain that is “non-specific” and there is no clearly identifiable pain generator that explains the pain, and (3) chronic pain that is due to some type of nerve damage or abnormal nervous system reaction.

Chronic Pain Associated with a Progressive Disease

In chronic pain associated with a progressive disease there is an ongoing disease process that is causing the pain. This might include such conditions as cancer, COPD, muscle spasm in multiple sclerosis, etc. These conditions are often actually categorized by disease state (e.g., cancer pain) and this dictates special evaluation and treatment approaches.

Chronic Non-cancer Pain

Several terms have been developed for chronic pain in which a specific disease process or pain generator cannot be identified or does not account for the level of pain and suffering being reported by the patient. These include chronic pain, chronic benign pain, chronic non-cancer pain, and chronic non-specific pain. For the purposes of this discussion we will simply use the term “chronic pain”. In this type of chronic pain, the problem may have started with an acute injury or trauma (e.g., back injury, etc) and developed into a chronic pain problem of more than 6 months duration such as chronic non-specific low back pain, fibromyalgia, etc.

It appears that pain can set up a pathway in the nervous system and, in some cases this becomes the problem in and of itself. In this type of chronic pain the nervous system may be sending a pain signal even though there is no ongoing tissue damage, or the tissue injury (e.g., pain generator) is less than what would be expected given the patient’s pain experience. The nervous system itself misfires and creates the pain. As we shall discuss, the pain signal from the peripheral nervous system is enhanced by higher level central nervous system processes. In such cases, the pain is the disease rather than a symptom of an injury.

Chronic Neuropathic Pain

Neuropathic pain has only been investigated relatively recently and seems to involve some type of direct injury to the nerves. In most types of neuropathic pain, all signs of the original injury are usually gone and the pain that one feels is unrelated to an observable injury or condition. With this type of pain, certain nerves (that have been injured or irritated) continue to send pain messages to the brain even after the initial tissue damage has healed.

Neuropathic pain (also called nerve pain or neuropathy), is very different from pain caused by an underlying injury. While it is not completely understood, it is thought that injury to the sensory or motor nerves in the peripheral nervous system can potentially cause neuropathy. Neuropathic pain is placed in the chronic pain category but it has a different feel then chronic pain of a musculoskeletal nature.

Neuropathic pain feels different than musculoskeletal pain, and is often described with the following terms: severe, sharp, lancinating, lightning-like, stabbing, burning, cold, and/or ongoing numbness, tingling or weakness. It may be felt traveling along the nerve path from the spine down to the arms/hands or legs/feet. Different types of neuropathic pain conditions include reflex sympathetic dystrophy (or Complex Regional Pain Syndrome), trigeminal neuralgia, postherpetic neuralgia, radiculopathy, etc.

CHRONIC PAIN VERSUS ACUTE PAIN

Unfortunately, many physicians still treat all pain as acute pain using a unilateral medical model. Medical evaluation of acute pain might involve extensive diagnostic testing such as MRI, CT, and diagnostic nerve blocks to determine the cause of the pain (or “pain generator”). Treatment often includes medications, physical immobilization, invasive procedures, and surgery to try to correct the source of the pain. The medical approach is generally quite appropriate in acute pain cases (e.g., repair the bone fracture, torn muscle or herniated disc). However, this strictly bio-medical approach can be exactly the wrong thing to do in cases of chronic non-specific pain. In fact, treating non-specific chronic pain as if it were acute pain will likely make the patient worse since it reinforces the sick role and subjects the patient to iatrogenic problems. In addition, treating the other type of chronic pain problems (progressive disease, neuropathies) strictly from a medical model is also inappropriate. It is important to keep in mind that any type of chronic pain problem (and acute pain problem for that matter) is susceptible to the influence of psychosocial factors.

It is critical for the physician and patient to have an understanding of the difference between acute and chronic pain. Evaluation and treatment approaches will be different depending upon the type of pain problem.

THEORIES OF PAIN

Old Ideas: The Specificity Theory of Pain

Rene Descartes proposed one of the original theories of pain in 1664. His theory proposed that a specific pain system carried messages directly from pain receptors in the skin to a pain center in the brain. He suggested that it is like a bell-ringing mechanism in a church such that a man pulls the rope at the bottom of the tower  and the bell rings at the top. In this model there is a one-to-one relationship between tissue injury and the amount of pain a person experiences. For instance, if you stick your finger with the needle you would experience minimal pain; whereas, if you cut your hand with a knife you would experience much more pain. Thus, the specificity theory proposes that the intensity of pain is directly related to the amount of tissue injury. The specificity theory underwent modifications throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries but its basic assumptions were unchanged (See Melzack and Wall, 1973, for a discussion of other pain theories including Muller’s doctrine of specific nerve energies, 1842; Von Frey’s theory, 1894; pattern theories, various theorists from 1894 through the mid-1950’s; Livingston’s central summation theory, 1943; and, Noordenbos’ sensory interaction theory, 1959). and the bell rings at the top. In this model there is a one-to-one relationship between tissue injury and the amount of pain a person experiences. For instance, if you stick your finger with the needle you would experience minimal pain; whereas, if you cut your hand with a knife you would experience much more pain. Thus, the specificity theory proposes that the intensity of pain is directly related to the amount of tissue injury. The specificity theory underwent modifications throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries but its basic assumptions were unchanged (See Melzack and Wall, 1973, for a discussion of other pain theories including Muller’s doctrine of specific nerve energies, 1842; Von Frey’s theory, 1894; pattern theories, various theorists from 1894 through the mid-1950’s; Livingston’s central summation theory, 1943; and, Noordenbos’ sensory interaction theory, 1959).

The specificity theory is generally accurate for acute pain, but it does not explain many types of chronic pain. Unfortunately, variations on the specificity theory are still taught (or at least emphasized) in many medical schools and a majority of doctors still ascribe to it in practice. The theory assumes that if surgery or medication can eliminate the alleged “cause” of the pain, then the pain will disappear. In chronic pain cases, this is very often not true. If a doctor continues to apply the specificity theory to a chronic pain problem the patient is at risk for getting surgeries, medicines and procedures that will not work as the search for the “source of the pain” presses on. Ultimately, the validity of the patient’s pain complaints will be challenged if reasons cannot be found and the “treatments” do not work.

Problems with the Specificity Theory

Several research findings and clinical observations have proven the specificity theory to be inadequate and these can be summarized as follows (See Wall and Melzack, 1973; Turk and Gatchel, 2002, for a more detailed discussion):

The meaning of the situation influences pain. Dr. Henry Beecher worked with severely wounded soldiers during World War II. To his surprise, Dr. Beecher observed that only one out of three soldiers carried into a combat hospital complained of enough pain to require morphine. Most of the soldiers either denied having pain from their significant injuries or had so little pain that they declined medication. These soldiers were not in a state of shock nor were they unable to feel pain since they complained when the IV lines were placed.

When Dr. Beecher returned to his practice in the United States after the war he noticed that trauma patients with wounds similar to the soldiers he had treated required morphine to control their pain at a much higher rate. In fact, four out of five patients required morphine for pain from wounds similar to those he had seen in the combat soldiers. Dr. Beecher concluded that this evidence demonstrated there was not a direct relationship between the wound and the amount of pain experienced. He believed the meaning attached to the injuries in the two groups explained the different levels of pain. To the soldier, the wound meant thankfulness to escape alive from the battlefield and to be going home. Alternatively, the injury to a civilian often meant major surgery, loss of income, loss of activities, and many other negative consequences.

Pain after healing of an injury. Another finding that discounted the specificity theory was that of phantom limb pain. Many times patients who undergo the amputation of a limb continue to report sensations that seem to come from the limb that has been amputated. This might include feeling that the limb is still there, or it may be a sensation of pain. Of course, the sensations cannot be actually coming from the limb since it has been removed from the person’s body. The specificity theory cannot account for these findings since there is no ongoing tissue injury in the amputated limb.

Injury without pain and pain without injury. Injury without pain can occur in a variety of situations including individuals who are born without the ability to feel pain. These patients must learn to avoid damaging themselves severely since there is no “protective function” from pain. The following is just such a case as reported on CNN.com Health (November 1, 2004):

|

Case Example: Injury Without Pain

|

|

If 5-year-old Ashlyn's chili is scalding hot, she'll gulp it down anyway. On the playground, a teacher's aide watches Ashlyn closely, keeping her off the jungle gym and giving chase when she runs. If she takes a hard fall, Ashlyn won't cry. Ashlyn is among a very small group of people in the world known to have congenital insensitivity to pain with anhidrosis, or CIPA -- a rare genetic disorder that makes her unable to feel pain. The untreatable disease also makes Ashlyn incapable of sensing extreme temperatures -- hot or cold -- disabling her body's ability to cool itself by sweating. The genetic mutation that causes CIPA only disrupts the development of the small nerve fibers that carry sensations of pain, heat and cold to the brain.

|

Another fairly common situation is a person being distracted when injured such that pain is not felt. In this case, it is not uncommon to hear stories of accident victims presenting to the emergency room stating they were injured (including major lacerations of the skin and fractured bones) but did not experience pain until minutes or hours afterwards.

Pain without injury or after the point of complete tissue healing can occur in a number of medical conditions such as central neuropathic pain after a stroke, reflex sympathetic dystrophy (complex regional pain syndrome), phantom limb pain, and post-herpetic neuralgia.

Hypnosis for anesthesia. The specificity theory cannot explain how hypnosis can be used for anesthesia during surgery. Certain people under hypnosis can withstand high levels of pain that would normally cause them to cry out. Surgery has been done on almost every part of the body using only hypnosis for anesthesia. Obviously, significant tissue damage is occurring during the surgery but the patient under hypnosis is not experiencing any pain. This finding dealt the specificity theory its final blow!

NEW IDEAS: THE GATE-CONTROL THEORY OF PAIN

Due to the findings listed previously a new theory of pain was developed in the early 1960’s that could explain these results. It is called the gate control theory of pain and it was developed originally by Melzack and Wall (1965). The gate control theory changed the way in which pain perception was viewed. The original theory is very complex and a detailed discussion is beyond the scope of this presentation. However, it will be valuable to present an overview of the theory in language that can be used with patients. Explaining the basics of this theory to patients can help establish the credibility of psychological pain management interventions. It will also demonstrate to the patient that the psychological intervention can actually change (decrease) the experience of pain on a physiological level.

The gate control theory attempts to explain the experience of pain (including psychological factors) on a physiological level. Based upon subsequent challenges and findings, the original gate control theory has undergone some reformulation and revision but the basic tenets hold true. It has been able to explain a variety of pain phenomena and has had enormous heuristic value in stimulating further research (Turk and Flor, 1999).

In the gate control theory, pain is divided into two components which are processed by the body separately. These are:

· the peripheral nervous system which is outside of the brain and spinal cord, and

· the central nervous system which includes the spinal cord and the brain.

Pain messages flow along the peripheral nerves to the spinal cord and proceed to the brain. In the spinal cord there are “nerve gates” (in the dorsal horn substantia gelatinosa) that can inhibit (close) or facilitate (open) nerve impulses going from the body to the brain. These nerve gates are influenced by a number of factors including the diameter of the active peripheral fibers converging in the dorsal horns as well as “instructions” coming down from the brain.

The relative excitatory activity in the afferent large-diameter (myelinated) and small-diameter (unmyelinated nociceptor) fibers is thought to influence the spinal gates. The activity in the A-beta (large diameter) is thought to primarily inhibit transmission (close the gates) whereas the A-delta and C (small diameter) activity are thought to primarily facilitate transmission (open the gate). When the gates are more open, a person experiences more pain since the messages flow freely. When the gates close, the pain is decreased or may not be experienced at all. The specifics of each part of the pain system are discussed in the following paragraphs. These are important concepts because they explain why various treatments are effective.

The Peripheral Nervous System

This will be a brief review of your graduate course in psychophysiology. Sensory nerves bring information to the spinal cord from various parts of the body. These nerves are specialized to detect: pain, heat, cold, vibration, and touch. At least two types of small diameter nerve fibers are thought to carry the majority of pain messages to the spinal cord:

· A-delta nerve fibers carry electrical messages to the spinal cord at approximately 4 to 44 meters per second (“first” or “fast” pain).

· C-fibers carry electrical messages at approximately .5 to 1 meter per second to the spinal cord (“slow” or “continuous pain”).

As discussed previously, the activity of the A-delta and C fibers tend to facilitate transmission of the nerve impulse (“open” the spinal nerve gates). In addition, they result in a different pain sensation. A good example of how these different nerve fibers work is when you strike your “funny bone” in your elbow (actually the ulnar nerve). You may notice that the first sensation is a sharp, tingling pain followed by a second sensation of achiness. The first sensation is the activation of the A-delta nerve fibers followed by the activation of the slower C-fibers. The activation of different nerve fibers can produce different qualities of pain sensation.

Also, you may have noticed that when you strike your elbow or hit your head, rubbing the area seems to provide some relief. This is because you are activating other sensory nerve fibers. These nerve fibers carry pressure and touch messages to the spinal cord:

· These fibers are called “A-beta fibers” and they send their message at approximately 93 to 103 meters per second.

These speeding messages can reach the spinal cord and brain to override some of the pain messages carried by the A-delta and C-fibers. When this overriding occurs, the pain messages are decreased and you experience less pain. The action of these differing nerve fibers can explain why many treatments for pain are effective. Treatments such as massage, heat, cold, TNS (transcutaneous nerve stimulation), or acupuncture can change a pain message due to some of these differences in nerve fibers.

The Spinal Cord

The pain message travels along the peripheral nervous system until it reaches the spinal cord. At this point, an extremely complex system can:

· Send the message directly to the brain

· Change the message being sent to the brain

· Stop the message from reaching the brain

As discussed previously, the gate control theory proposes that there are gates on the bundle of nerve fibers in the spinal cord between the peripheral nerves and the brain. These spinal nerve gates can either open to allow pain impulses to move freely from the peripheral nerves to the brain, or they can close to stop the pain signals from reaching the brain. Many factors determine how the spinal nerve gates will manage the pain signal including:

· The intensity of the pain message

· The competition from other incoming nerve messages (such as touch, vibration, heat, etc)

· Signals from the brain telling the spinal cord to increase or decrease the priority of certain pain messages.

The Brain

Once the pain signal reaches the brain, a number of different things can happen. Certain parts of the brain stem can inhibit or muffle incoming pain signals by the production of endorphins, which are naturally occurring morphine-like substances. Stress, excitement, and vigorous exercise are among the things that may stimulate the production of endorphins. This is why athletes may not notice the pain of a fairly serious injury until the “big” game is over. This is also why regular aerobic exercise can be an excellent method to help control chronic pain.

In addition, pain messages may be directed along different pathways in the brain. For instance, a fast pain message is relayed by the spinal cord to specific locations in the brain: the thalamus and cortex. A fast pain message reaches the cortex quickly and prompts the individual to take action to reduce the pain or threat of injury.

In contrast, chronic pain tends to move along a “slow pain” pathway. As discussed above, slow pain tends to be perceived as dull, aching, burning, and cramping. Initially, the slow pain messages travel along the same pathways as the fast pain signals through the spinal cord. Once they reach the brain, the slow pain messages take a pathway to a different portion of the brain, the hypothalamus and the limbic system. The hypothalamus is responsible for the release of certain stress hormones in the body. The limbic system is the brain area where emotions are processed. As shall be discussed later, this is one reason why chronic pain is often associated with stress, depression, and anxiety. The slow pain signals are actually passing through brain areas that control these experiences and emotions.

As discussed previously, the brain also controls pain messages by attaching meaning to the situation in which the pain is experienced. This occurs in the cortex, which is a higher level of the brain where thinking takes place. As reviewed previously, soldiers who were wounded in combat displayed much less pain then similarly wounded civilians who had been involved in a trauma such as a car accident. The meaning that the brain attached to the situation seemed to be the important difference. The brain also gives meaning to the pain signal and this occurs in the cortex. Depending on how the messages are received and other factors related to the situation, the brain may pay close attention to the pain signal, or choose to ignore it altogether.

DOWN THE PAIN PATHWAYS

So far we have primarily focused on factors that influence the pain signal as it travels from the periphery to central structures (afferent input). In addition to these influences, the pain signal can be influenced by efferent neural impulses that descend from the brain. In other words, the brain can send signals down the spinal cord to open and close the nerve gates. At times of anxiety or stress, the descending messages from the brain may actually amplify the pain signal at the nerve gate as it moves up the spinal cord. On the other hand, the descending message from the brain can “close” the nerve gate in the spinal cord and the message will be stopped at the closed nerve gate (no pain experienced by the brain). This can occur in situations such as being in battle, playing competitive sports, being under hypnosis, being distracted, etc.

Opening and Closing the Pain Gates

In working with chronic pain patients it is important to carefully explain the gate control theory of pain along with providing examples as previously discussed. This provides an excellent foundation to discuss what factors can open and close the spinal nerve gates. The following presentation can be helpful for patients:

Let's look at a number of other things that can open or close the pain gates as messages move up and down the spinal cord. These can be divided into sensory, cognitive, or emotional areas:

Sensory factors include things that are related to your actual physical being and activities.

Cognitive factors are those things that are related to your thoughts. This might include your memories, your interpretation of a current situation, or your predictions about the future.

Emotional factors are those things related to your emotions or feelings. Emotions are being happy, sad, mad, or glad.

Some examples of sensory, cognitive, and emotional factors that influence pain perception can be seen in the following table.

|

Opening and Closing the Pain Gates

|

|

Factors that open the pain gates and cause more suffering are:

Sensory factors are such things as injury, inactivity, long-term narcotic use, poor body mechanics, and poor pacing of your activities.

Cognitive factors are focusing on the pain, having no outside interests, worrying about the pain, remembering bad things associated with the pain, and thinking that your future is a catastrophe.

Emotional factors include depression, anger, anxiety, stress, frustration, hopelessness, and helplessness.

Factors that close the pain gates and cause less suffering are:

Sensory factors can include increasing your activity, short-term use of pain medication, relaxation training and meditation, as well as aerobic exercise.

Cognitive factors include outside interests, thoughts that help you cope with the pain, and distracting yourself from the pain.

Emotional factors that can close the pain gates include having a positive attitude, decreasing depression, being reassured that the pain is not harmful, taking control of your pain and your life, and stress management.

|

The following illustration is helpful for patients to understand the gate control theory of pain.

PATIENT EXAMPLES: THE GATE CONTROL THEORY IN ACTION!

The following examples can be presented to patients to help illustrate two things: (1) how the brain can selectively block out sensations it perceives as non-threatening and (2) the gate control theory in action.

You may notice that when you first get dressed you can feel the physical sensations that result from the clothing. This is especially true for the typically tighter fitting items such as underwear and shoes as they press against your body. After you have had your clothes on for even a brief period of time, the physical sensations are not noticeable at all unless you specifically pay attention to them. This is an example of how the brain blocks out sensations that it knows are not dangerous.

The next two examples relate directly to pain problems. Imagine that a tight clothespin has been placed on your arm and you are instructed to leave it there for the entire day. For those of you with masochistic tendencies, go ahead and try this experiment for yourself rather than just using your imagination. The initial pain from the tight clothespin might be quite severe as it compresses your skin and surface muscles. Peripheral nerve fibers sense this pressure and transmit a pain signal to the spinal cord and on to the brain. At first you'll notice a fast pain, but then after a while you may notice a slow pain. Initially the pain is experienced as fairly proportional to the amount of pressure applied. Everyone would agree that this is acute pain.

After a short while, the pain messages coming from the clothespin will begin to be decreased by the closing of the spinal nerve gates. This is because the brain begins to view the pain signals as non-harmful and not a threat. The pressure from the clothespin may be painful initially but it is not injuring you in any way. As time goes on, the pain message is given less priority by the brain and your awareness of it decreases greatly. The brain knows that the clothespin will be there all day long and it is not causing any injury. Therefore, the brain gradually “turns the volume down” on the pain message to the point of it being barely noticeable after about thirty minutes. The compression on your skin is still occurring, but it is now perceived as either a mild discomfort or not noticed that all.

The last example is one that occurs frequently at our spine center. Just recently, a female patient came in convinced that her back pain was due to a spinal tumor. A thorough physical examination and medical history was entirely normal except for the onset of the back pain after a recent period of extreme stress. The stress involved the patient’s elderly father who had recently been diagnosed with (you guessed it) a spinal tumor. The patient reported that her father’s symptoms had also initially been back pain. Upon questioning, it became quite clear that the patient had an extreme fear that she also was suffering from a spinal tumor. This belief was creating intense suffering, which in turn, made the back pain worse. An MRI was obtained and shown to be negative, and the diagnosis above, stress related back pain, was made. After experiencing tremendous relief that the back pain was not the result of a tumor (in addition to one or two jumps of joy), the patient’s symptoms began to dissipate rather rapidly and she returned to normal activities. In this case, the patient’s anatomy had not changed, just her beliefs about the cause of the pain.

WHEN ACUTE PAIN BECOMES CHRONIC

Not all pain that persists will turn into chronic pain. Pain is experienced very differently for different people. Likewise, the effectiveness of a particular treatment will often differ from person to person. For example, a particular medication or injection for a herniated disc may provide effective pain relief for some people but not for others.

Not all patients with similar conditions develop chronic pain, and it is not understood why some people will develop chronic pain and others will not. Also, a condition that appears relatively minor can lead to severe pain, and a serious condition can be barely painful at all.

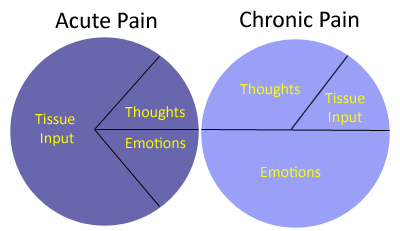

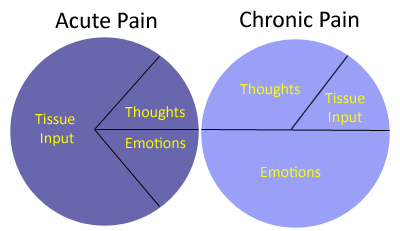

As pain moves from the acute phase to the chronic stage, influences of factors other than tissue damage and injury come more into play. Also, influences other than tissue input become more important as the pain becomes more chronic. These include such things as ongoing “pain” signals in the nervous system even though there is no tissue damage, as well as thoughts and emotions, as discussed previously. This can be a difficult concept for chronic pain patients to accept. A common retort is, “but my pain is real”. Remember, as we discussed at the beginning of this section, all pain is real and physically experienced. But, the gate control theory establishes that pain can be affected by a variety of factors other than tissue input. After a discussion of the gate control theory and some of these examples, patients are often more open to accepting the idea of psychological pain management treatment.

CHRONIC PAIN AND SUFFERING

“Those who have something better to do, don't suffer as much”. – W. Fordyce, Ph.D.

There are many things that can increase or decrease a patient’s perception of pain. These influences on pain perception are explained by the gate-control theory. This section will be a further discussion of these issues, as it is an area most commonly neglected in traditional approaches to chronic pain. These factors  are well known to the research and academic communities but rarely acknowledged in general practice. The concepts presented in this section are excellent to discuss with the chronic pain patients. are well known to the research and academic communities but rarely acknowledged in general practice. The concepts presented in this section are excellent to discuss with the chronic pain patients.

The Pain System

As explained by the gate control theory of pain, there is not a one-to-one relationship between tissue damage and pain, as the specificity theory postulated. Rather, many factors influence chronic pain, disability, and suffering. Thus, a person can have severe pain with minimal physical findings and minimal pain with horrendous physical findings. The “onion” model describes in a simple format what is currently known about aspects of chronic pain. The model makes common sense given the examples discussed in the previous section such as hypnosis and phantom-limb pain. In using this model with patients they can immediately understand the importance of addressing all aspects (or “layers”) of the chronic pain problem. The following are definitions of the various "layers" of pain in the model. The diagram depicts the pain system and the various influences on chronic pain. Tissue damage is only one of many factors determining how much pain will be experienced. This pain system model is excellent for use in working with chronic pain patients.

THE MULTI-FACTORIAL NATURE OF PAIN AND SUFFERING

Tissue Damage or Nociception

This is defined as mechanical, thermal (heat or cold), or chemical energy acting on specialized nerve endings that send an impulse, or "signal," into the nervous system that negative events are occurring. The “transduction” of tissue trauma into neural signal depends upon sensory end organs known as nociceptors (Chapman, Nakamura, & Flores, 1999). Nociceptors are sensory neurons found throughout the body. As discussed previously, these nociceptors consist of:

· A-delta fibers

o conduct impulses at 4 to 44 meters per second

o thinly myelinated

o function as thermal and/or mechanical nociceptors

o produce pain sensation that is sharp or pricking

· C-fibers

o conduct impulses slowly (.5 to 1 meters per second)

o unmyelinated

o polymodal receptors that respond to various high-intensity mechanical, chemical and thermal stimuli.

o produces pain sensation that is burning or aching

Both of these types of fibers are distributed widely in skin and deep tissues. These nociceptors are usually the beginning point of the "pain" message. Pain is produced by repetitive stimulation of these receptors. It might include an impact or trauma (mechanical, such as cutting yourself), an injury involving temperature (thermal, such as burning yourself), or an injury involving chemical changes (chemical, such as an irritant). Nociception is what occurs at the site of injury that usually leads to pain being experienced. For instance, if you have ever hit your finger with a hammer or struck your toe on a table, you may have noticed that the pain signal can take a brief moment to reach your brain and be experienced.

Pain Sensation

In the simplest terms of this model, pain is the actual perception that occurs in the brain after the nerve signal (due to nociception) travels from the periphery to the central nervous system. Pain sensation is experienced in the brain, while nociception occurs at the site of injury. However, it must also be kept in mind that a pain sensation can be experienced without nociception as discussed in the last section on phantom limb pain. In addition, there may be no pain sensation even with extensive nociceptive input (the severely wounded soldier or surgery under hypnosis).

Thoughts

Cognitions or thoughts occur in higher brain centers and are an assessment of the pain sensation signal coming into the nervous system as well as events surrounding it. These thoughts can be conscious or unconscious and will greatly influence how the pain signal is perceived. For instance, general body aches and stiffness are perceived as "good pain" when these occur after a vigorous exercise session, whereas they are perceived as "bad pain" when related to a medical condition, such as fibromyalgia. The level of actual input to the nervous system may be the same, but the thoughts about the input cause the pain in the patient with fibromyalgia to be perceived as much more distressing.

Another example was experienced by Dr. Deardorff. As a teenager he was struck in the face by a door, causing a significant injury with profuse bleeding that required forty stitches. Interestingly no pain was experienced until the extent of the injury was realized by seeing the reaction of others and looking in the mirror. After that the pain became quite intense. These examples illustrate how thoughts (conscious and unconscious) impact pain perception and suffering. The thoughts were generally of the nature, "Oh, this must be very serious!" which made the pain worse.

In the case of chronic back pain (and other chronic pain conditions) a similar assessment of the situation occurs in the patient. Many patients are convinced that their chronic pain represents serious damage even though physical findings are minimal. They believe that “hurt equals harm” and are totally guided and controlled by the pain. In these people suffering is very great. Alternatively there are people (a smaller group by far) who have very severe findings on their diagnostic tests (e.g., MRI, CT of the spine) yet who don't seem to be bothered by the pain. They perceive their pain as benign or not dangerous. They live their lives regardless of the pain, and overall suffering is thereby diminished. Thus, these differences in pain sensation can be explained by differences in thoughts and attitudes about the pain.

Changing a patient’s thoughts about his or her chronic pain through cognitive behavioral treatment is one of the most powerful psychological treatment tools and this will be discussed in the second course, Evaluation and Treatment.

Emotions

The emotional aspect of pain is a person’s response to thoughts about the pain. If you believe (thoughts) the pain is a serious threat, then emotional responses will include fear, depression, and anxiety, among others. Conversely if you believe the pain is not a threat, then the emotional response will be negligible. Consider, again, the previous example of a strenuous workout. The day afterward the person may show grimacing, slow movements, and other "pain behaviors." Even so, the thoughts about the pain will be positive ("Boy, what a good workout that was last night") and the emotions will follow similarly (e.g., feeling good about having worked so hard). The thoughts and subsequent emotional response would be quite different in the case of a fibromyalgia flare-up even though the nociceptive input and pain behaviors are similar. We will discuss the emotional aspects of pain in more detail later in this section.

Suffering

As discussed by Morris (2003), the term “suffering” is often used as a synonym for “pain” even though they are theoretically and conceptually distinct. As Morris (2003) discusses, a broken bone may cause pain without suffering or a great level of suffering. When faced with the same level of nociceptive input, understanding why one individual will demonstrate a great level suffering while another will show minimal suffering is critical to the evaluation and treatment of chronic pain. Unfortunately, the theoretical and conceptual distinction between pain and suffering is often neglected in clinical practice, which can negatively impact the evaluation and treatment of the patient’s condition. As will be discussed in detail in the chronic pain treatment course, we will often very explicitly tell the chronic pain patient that our intervention will actually be focused on decreasing his or her level of suffering rather than the pain. Frequently, the patient shows relief and optimism in response to this formulation since they have already had many failure experiences relative to treatments targeting the pain. We also explain that decreasing their level of suffering and improving their quality of life will, in turn, help diminish their perception of pain.

Suffering is very closely tied to the emotional aspect of pain. In general it is triggered by aversive events, such as loss of a loved one, fear, or a threat to one's well-being. Suffering very often occurs in anticipation of a possible perceived threat even though the threat may or may not actually exist. A very good example of this last scenario is similar to what was presented in the last section. A patient with severe headaches was firmly convinced she had a brain tumor. Her husband had recently died of a brain tumor that had started with simple headaches. Her suffering was very high, since she was anticipating her head- aches were a sign of a very serious condition that could lead to death. After the MRI it was confirmed that she did not have a tumor and that her headaches were likely due to muscle tension. Her suffering decreased significantly, as did her pain. This illustrates extreme suffering in response to a threat that never actually existed. It also illustrates how a patient’s level of suffering can change even when the nociceptive input and pain sensation do not.

Pain Behaviors

Pain behaviors are defined as things people do when they suffer or are in pain. These are behaviors that others observe as typically indicating pain, such as the following:

· talking or complaining about the pain

· grimacing, moaning, crying, limping, moving slowly

· taking pain medicine, rubbing a painful area

· moving more slowly, asking for help, lying down

· avoidance of certain activities, seeking further treatment

Pain behaviors are in response to all the other factors in the pain system model (tissue damage, pain sensation, thoughts, emotions, and suffering). Pain behaviors are also affected by previous life experiences, expectancies, and cultural influences in terms of how the pain is expressed. Interestingly pain behaviors are also affected by the outside environment, as will be discussed in the next section.

Psychosocial Environment

Psychosocial environment include all of the environments in which we live, work, and play. Research has consistently shown that these environments influence how much a person will show pain behaviors. One might also expect that pain behaviors will vary across the different psychosocial environments of the patient. Chronic pain can affect all aspects of a person's life including relationships, work activity, sexual functioning, recreational pursuits, and so on. Exactly how these environments can affect the patient’s pain and suffering are important to evaluate since this can help guide the treatment intervention.

FACTORS INFLUENCING ACUTE AND CHRONIC PAIN

As we discussed in the previous section, pain can generally be divided into acute and chronic phases based upon the length of time in pain and how fast the tissues are expected to heal. It is very important to understand that as pain moves from the acute to the chronic stages, the influences of other factors in the pain system (aside from tissue damage) come more into play. Gatchel (1991, 1996, 2004) has characterized this progression from acute to chronic pain as both mental and physical deconditioning. Physical deconditioning is the result of disuse, medication use, muscle weakness and other factors. Mental deconditioning is depression, anxiety, helplessness and hopeless as a result of such things as fear of the pain, loss across a number of psychosocial environments, etc. The model suggests physical and mental re-conditioning as viable treatments.

This model can be applied to a number of chronic pain problems, especially those of a musculoskeletal nature. As discussed in the model, as the pain goes on longer and longer, factors other than tissue input become more influential. This can be a difficult concept for patients to understand, and the common retort is, "But I have real pain." Again, as a reminder, the pain is absolutely real and is physically experienced. It is simply being supported and increased by factors other than the tissue damage. Another conceptual model of the various factors influencing acute versus chronic pain can be seen in the figure.

As we discovered in the pain system model, thoughts, emotions, and suffering are an integral part of any chronic pain experience. In this section we will further investigate how emotions influence pain and vice versa. These emotions include depression, anxiety, fear, and anger.

CHRONIC PAIN AND DEPRESSION

Comorbid psychiatric disorders commonly occur in chronic pain patients and, of these, depression is common. Chronic pain and depression are two of the most common health problems that health professionals encounter, yet only a handful of studies have investigated the relationship between these conditions in the general population (Currie and Wang, 2004). For instance, major depression is thought to be four times greater in people with chronic back pain than in the general population (Sullivan, Reesor, Mikail & Fisher, 1992). In research studies on depression in chronic low back pain patients seeking treatment at pain clinics, prevalence rates are even higher. These range from 32 to 82 percent of patients showing some type of depressive problem, with an average of 62 percent (Sinel, Deardorff & Goldstein, 1996). In a recent study of chronic disabling occupational spinal disorders in a large tertiary referral center, the prevalence of major depressive disorder was 56% (Dersh, Gatchel, Mayer et al., 2006). In another study it was found that the rate of major depression increased in a linear fashion with greater pain severity (Currie and Wang, 2004). It was also found that the combination of chronic back pain and depression was associated with greater disability than either condition alone.

Depression is more commonly seen in chronic back pain problems than in those of an acute, short-term nature. The development of depression in these cases can be understood by looking at the host of symptoms often experienced by the person with chronic spine pain. Explaining this process to the patient can be very useful since it demystifies the etiology of the depression and dispels the idea that being depressed is somehow related to a “weak will”. We will often tell patients that clinical depression goes beyond normal sadness and is characterized by the following symptoms from the DSM-IV:

|

Symptoms of Clinical Depression

|

|

A predominant mood that is depressed, sad, blue, hopeless, low, or irritable, which may include periodic crying spells.

Poor appetite or significant weight loss or increased appetite or weight gain.

Sleep problem of either too much (hypersomnia) or too little (hyposomnia) sleep.

Feeling agitated (restless) or sluggish (low energy or fatigue).

Loss of interest or pleasure in usual activities.

Decreased sex drive.

Feeling of worthlessness and/or guilt.

Problems with concentration or memory.

Thoughts of death, suicide, or wishing to be dead.

|

It is often quite impactful to go over this list with the chronic pain patient since it can help develop a therapeutic alliance in treating the depression.

Chronic pain often results in difficultly sleeping which leads to fatigue and irritability during the day. During the day the chronic pain patient often has difficulty with most activities (moving slowly and carefully) as well as spending most of the time at home away from others. This leads to social isolation and a lack of enjoyable activities. Due to the inability to work, there may be financial difficulties that begin to impact the entire family. Beyond the pain itself, there may be gastrointestinal distress caused by anti-inflammatory medication and a general feeling of mental dullness from the pain medications. The pain is distracting leading to memory and concentration difficulties. Sexual activity is often the last thing on the person’s mind and this causes more stress in relationships. Understandably, these symptoms accompanying chronic pain may lead to feelings of despair, hopelessness, and other symptoms of a major depression.

A recent study by Strunin and Boden (2004) investigated the family consequences of chronic back pain. Patients reported a wide range of limitations on family and social roles including: physical limitation that hampered patients’ ability to do household chores, take care of the children, and engage in leisure activities with their spouses. Spouse and children often took over family responsibilities once carried out by the individual with back pain. These changes in the family often lead to depression and anger among the back pain patients and to stress and strain in family relationships.

Several psychological theories about the development of depression in chronic back pain focus on the issue of control. As discussed previously, chronic back pain can lead to a diminished ability to engage in a variety of activities such as work, recreational pursuits, and interaction with family members and friends. This situation leads to a downward physical and emotional spiral that has been termed “physical and mental deconditioning” (as discussed previously; See Gatchel and Turk, 1999). As the spiral continues the person with chronic back pain feels more and more loss of control over his or her life. The individual ultimately feels totally controlled by the pain leading to a major depression. Once in this depressed state, the person is generally unable to change the situation even if possible solutions to the situation exist.

Depression and Chronic Pain

The heading above is not a typo. We first discussed chronic pain leading to depression and we will now cover the idea that depression can predispose a patient to chronic pain.

For quite some time, clinical researchers have known that chronic back pain can lead to major depression, as discussed previously (See Worz, 2003 for a review). Newer studies are now looking at how psychological variables such as depression and anxiety may be linked to the onset of a back and other pain problem. For example, Atkinson, Slater, Patterson, Grant, and Garfin (1991), in a systematic study of depressed male Veterans Administration chronic pain patients, found that 42% of patients experienced the onset of depression prior to the onset of pain, whereas 58% experienced depression after the pain began. Polatin et al. (1993) reported that 39% of the chronic low back pain patients they evaluated displayed symptoms of pre-existing depression. More recently, in a review of research studies in this area, Linton (2000) found that in 14 of the 16 reviewed studies, depression was found to have increased the risk for developing back pain problems.

Depression and Spine Surgery

As we have seen, many chronic pain patients will experience clinical depression. In addition, these patients will also be faced with the option of elective surgery in an attempt to help the pain. Having some understanding of the impact of depression on surgery is important. The following will briefly address this issue relative to back pain and spine surgery; however, the conclusions are applicable to other chronic pain states.

Research has clearly demonstrated that non-physical variables such as depression, anxiety, thought patterns, and personality style can impact a spine surgery outcome (See Block, Gatchel, Deardorff & Guyer, 2003 for a review). Unfortunately, it appears that in many cases, having a major depression may not bode well for the outcome of a spine surgery. For instance, as discussed by Block et al. (2003), spine surgery patients who are clinically depressed pre-operatively may continue to display depressive symptoms post-operatively and these can negatively impact the surgery outcome. Particular symptoms that may impede post-operative recovery include such things as low motivation, sleep disturbance, slower healing time, difficulty with physical rehabilitation and inability to perceive improvements (Block et al, 2003; Deardorff and Reeves, 1997).

Block et al. (2003) discuss that, in looking at the issue of depression and spine surgery outcome it is important to consider whether the individual is experiencing a “reactive depression” or shows a pre-injury history of more chronic depression. A reactive depression is defined as depressive symptoms in response to the chronic back pain and associated problems (loss of work, friends, etc). Reactive depression occurs in back pain patients who have no previous history of depression. However, many chronic back pain patients have a history of problems with depression even before the onset of the back pain. As reviewed previously, individuals with chronic depression may be at greater risk for developing a low back pain condition. It is also likely that this same group is at greater risk for a poorer outcome to spine surgery (Block et al., 2003).

If you are working with a chronic pain patient with significant depression who is facing an “elective” surgery for his or her pain problem, you may want to recommend (to patients and surgeon) that consideration be given for postponing the surgery until the depression can be treated. Treatment for depression is often part of a preparation for spine surgery program (See Block et al., 2003; Deardorff and Reeves, 1997).

Treating Depression in the Chronic Pain Patient

One of the biggest problems in treating major depression in the patient with chronic pain is missing the diagnosis. This occurs for two reasons: the chronic pain patient often does not realize he or she is also suffering from a major depression and the doctor is not looking for it. Chronic pain patients will often define their problem as strictly medical and related to the pain. This is supported by a recent study, which found that individuals with chronic pain and depression went to their physicians 20% more often than a comparison group of non-depressed medical patients. In addition, depressed chronic back pain patients were 20% less likely to see a mental health specialist than medical patients without a pain problem (Bao, Sturm, & Croghan, 2003).

The depressive symptoms may be downplayed by the chronic pain patient who believes that, “just get rid of this pain and I won’t feel depressed” or that acknowledging depression is a sign of weakness in dealing with the pain. When the diagnosis of major depression in the chronic pain patient is missed or ignored, treatments strictly directed at the pain are much more likely to fail. As concluded by Ohayon and Schatzberg (2003), the presence of a chronic pain physical condition increases the duration of depressive mood and chronic pain patients seeking medical consultation should be routinely screened for a major depression.

Treatment of depression associated with chronic pain requires a specialized approach. It is generally accepted that the pain and the depression should be treated simultaneously in a multidisciplinary fashion. The treatment of clinical depression most often includes psychological interventions (e.g., counseling, relaxation training, etc) and anti-depressant medication. In a recent review of the research from 1980 through 2000 looking at treatment of depression it was found that the combined treatment approach (medication and psychotherapy) yielded better outcomes than either of the interventions alone (Pampallona et al., 2004). Simultaneously treatment directed at the chronic pain is critical. It has been found that chronic pain may interfere with depression improvement and this makes common sense. Treatment for the chronic pain might include such things as physical rehabilitation aimed at restoration of function, trying to “normalize” one’s life as much as possible even with the pain, appropriate medication management, among other things. Multidisciplinary treatment of the chronic pain and major depression will ultimately give the patient more of a sense of control over the pain and start a “positive spiral” toward physical and mental re-conditioning.

ANXIETY

In most cases, anxiety about the pain is more likely in the subacute stage while depression prevails with chronification. The subacute phase occurs after the acute phase but before the chronic stage. It usually occurs at about the three- to six-month range. At the acute stage the patient with pain generally feels a reasonable sense of hope that the pain will resolve within the near future. In the subacute phase and at the beginning of the chronic phase, one's thoughts and emotions about the pain begin to change. It is not uncommon for the person to begin to wonder, "Will this pain ever go away?" "This must be something serious," and "I'll never get better." These types of thoughts lead to anxiety.

Anxiety can occur at different intensities, all the way from nervousness to full panic attacks. We explain to patients that clinical anxiety is generally characterized by the following:

|

Symptoms of Anxiety

|

|

Muscle tension, including shakiness, jitteriness, trembling, muscle aches, fatigue, restlessness, and inability to relax

Nervous system overactivity, including sweaty palms, heart racing, dry mouth, upset stomach, diarrhea, lump in throat, shortness of breath, and so on

Apprehensive expectations, including anxiety, worry, fear, anticipation of misfortune

Trouble concentrating, including distractibility, insomnia, feeling "on edge," irritability, and impatience.

|

Although most patients believe that their anxiety will subside "when the pain goes away" the anxiety is very often causing a significant increase in pain perception. This results in a vicious cycle of pain, anxiety, more pain, and more anxiety. As an example of this, Dr. Deardorff recently evaluated and treated a seventy-two-year-old woman who had been scheduled to undergo spine surgery. She was clearly a good candidate for the surgery given all appropriate factors. As one part of her pain problem, she also had a significant amount of generalized anxiety. She had been involved in a few sessions of psychological preparation for surgery, which we will often do with anxious or depressed patients. Approximately two weeks prior to the scheduled surgery the patient's leg pain completely disappeared! Her findings on the MRI continued to be abnormal. The surgeon could only explain it under the category of "an act of nature one does not want to argue with." Given this experience, the patient expected that her anxiety and depression would also abate shortly thereafter. To her dismay this did not occur. She continued to be emotional and began to address those issues in psychotherapy.

This is certainly an unusual and rare example, but it does illustrate that removal of the pain does not necessarily mean emotional issues will also then resolve. For the patient to wait until the chronic pain is gone before addressing emotional issues is a trap that will prevent a return to a normal life.

FEAR AND PHOBIA

Recent research suggests that fear may be a significant component in many types of chronic pain. This fear is usually focused on the fear of further injury, increased pain, or both. This fear is often closely linked with anxiety as discussed in the previous section.

Fear in chronic pain is unreasonable when it is either not appropriate to the situation or is beyond what it should be, given the nature of the situation. This might include being fearful of reinjury when there is no indication that this will occur. When fear is at these levels and interferes with normal functioning, it is considered to be a phobia. A phobia is defined as an irrational fear of an object, activity, or situation causing the person to avoid the object, activity, or situation (e.g., movement).

A new area of scientific investigation in many types of chronic pain is “kinesophobia”, or fear of movement. In our clinical practice we see kinesophobia quite routinely. These patients have guarded, slow, and deliberate movements, as well as extreme cautiousness. This is often due not to the pain but rather to a phobia of injury, reinjury, or acute exacerbation. The following case example illustrates this condition.

|

Case Example

|

|

One case was a forty-two-year-old man who was a very successful lawyer. He had one episode of fairly severe back pain, somewhat localized, which lasted for quite some time. He attributed the onset of the pain to "moving a certain way" while getting out of his car. This had occurred about four months prior to the patient coming to our clinic. In that time he had been seen by several specialists, at least one of whom had recommended spine surgery. The patient came in with extremely slow, almost robot-like movements in an attempt to keep his spine as straight as possible. For fear of making the pain worse, he would not bend. He had developed a very structured ritual in order to get dressed each morning. This included putting his underwear and pants on the floor, stepping into them, and then gradually working them on with the help of a reaching device. He had developed similar rituals for putting his shoes on, driving, working at his desk, and interacting with his children. We ultimately involved him in an aggressive physical-therapy program for reactivation and mobility as well as psychological pain management to address his kinesophobia. We even employed such unusual techniques as having him do a type of obstacle course through the gym with a time clock so that he could not focus on his fear of the pain. There was no medical reason for him to fear the pain or to be a surgical candidate. The patient responded very well to the program with a return to normal activities.

|

Kinesophobia can cause great problems over the long term. The fear of movement results in the patient attempting to move as little as possible. This guarding behavior causes the muscles to fall into a state of disuse and atrophy. The muscles become weak and tight (shortened) due to lack of use. Any attempt to increase activity will then cause an increase in pain due to the weak and tight muscles. This scares the patient into not doing anything. Working through this  period of increased pain under supervision with reassurance is critical to recovery from the pain problem. period of increased pain under supervision with reassurance is critical to recovery from the pain problem.

Development of the disuse syndrome and physical/mental deconditioning due to fear of injury and pain, the cycle causes more and more pain to occur as can be seen in the Figure.

ANGER

Anger is frequently an integral component of chronic pain problems. It is helpful to explain to patients that anger may be felt and expressed directly or indirectly. We are all familiar with the direct expression of anger. This might include such things as a short temper, irritability, and explosive behavior, among other things. Indirect anger may be expressed in a number of ways. For instance depression has been defined as "anger turned inward" and may in some cases be a type of indirect anger. We often see chronic pain cases where there is no overt anger but an increase in self-destructive behaviors, such as increased smoking, coffee intake, risk taking, and substance abuse (alcohol and/or medicines). These patterns can indicate indirect anger. Another expression of indirect anger is passive aggressiveness. This is anger expressed outwardly but in a passive, indirect manner. It important to investigate how the patient might be using pain and disability in a passive aggressive manner. An example of this includes an increase in pain (or pain behaviors) in response to someone you are actually angry at. We commonly see this pattern in marital or family relationships. Usually the person with chronic pain who is expressing anger through increased pain does so unintentionally and is not aware of the pattern. Consider the following case example:

|

Case Example

|

|

I once treated a man with chronic low back pain who had not responded to the usual conservative interventions. As part of the multidisciplinary program he became involved in pain management treatment with a psychologist. As part of these treatment sessions the spouse is often brought in to help determine how the family is responding to the pain problem. Initially the couple stated that they "rarely fight" and that the pain problem had not really bothered them that much. This was in the face of also reporting that the man had been disabled from work, they had not had sex in over six months, and that she had had to get a job to help support the family due to his disability.